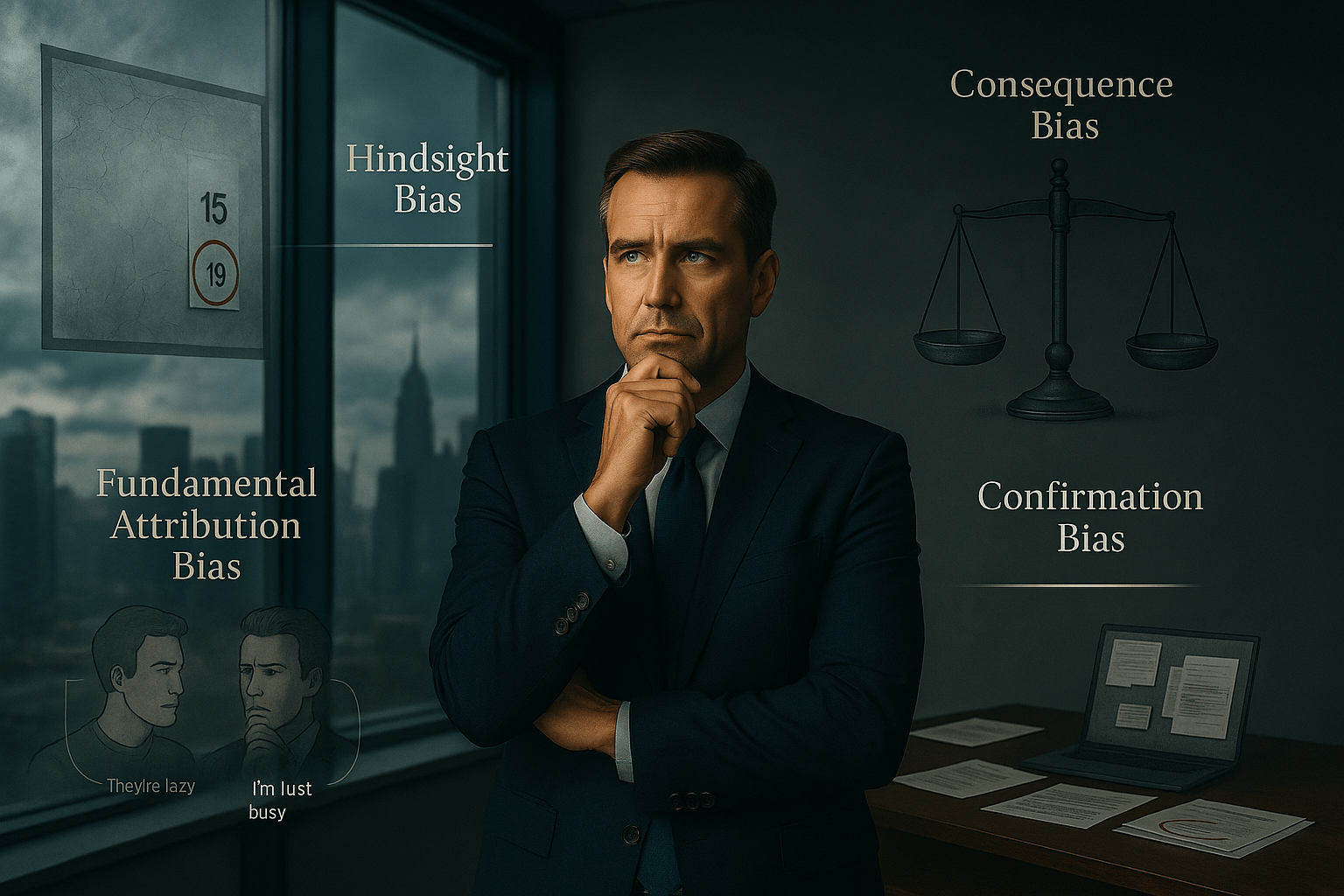

4 Cognitive Biases all leaders should know

We humans like to think that we are entirely rational creatures. That our decisions are logical, carefully considered and reasonable. Unfortunately while we certainly can reason, our decisions and actions are not purely the product of logical analysis, but influence by emotions, our physical state, and all sorts of cognitive distortions and biases. We cannot eliminate these things, nor would we want to, they are part of what makes us human. However we can be aware of their influence and have strategies in place to mitigate them where that have negative effects.

In this blog post I'll focus on four cognitive biases. Tendencies that influence our thinking. I'll discuss the impact they have and how we can mitigate them.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight Bias is the tendency for events to appear obvious to us when we look back after the fact. When we look towards the future, we can see all sorts of potential events that might happen. Some appear to be more likely than others. What ultimately happens might be one of those, but it might not. To quote Yoda from the Empire Strikes Back, "difficult to see, always in motion is the future." It's a hazy picture, full of uncertainty with many factors in play. Some of these we know, many we do not.

By contrast, when we look back at the past, there is only what happened, only one path. We are in possession of much more of the facts, and we can see why the events occurred as they did. It's like being at the top of a mountain and being able to all the way down.

When looking back at the past, knowing what we know in the present, it's very difficult for us to put ourselves in the mindset of someone without that perspective. How can you pretend to forget you know something? It's easy for us to think because something is obvious now, that it was equally obvious before, but this is often not true. We recognise its significance because we know the outcome, those people at the time did not, and therefore the significance may not have been obvious. Because we know what happened, we can overtook the other potential consequences that might have appeared more significant at the time.

It's therefore important that when we as leaders are assessing people's actions and decisions, that we try to put ourselves in their shoes with the knowledge they had at the time. We should be cautious before labelling someone as "reckless" or "inattentive", thinking we would have done better. It doesn't mean we cannot or shouldn't make assessments, but we should as far as we can do so based on how things appeared at the time, before the outcome was known. Asking questions like "why did what they did make sense at the time?", can help build that context.

Consequence Bias

Consequence bias is the tendency to judge a person's action or decision based purely on whether the outcome was good or bad. The better the outcome, the better the decision or action was, conversely, the worst the outcome, the worse the decision or action. However, this also is not always true. Human beings can generally control their actions and decisions, but are usually not in control of the outcomes that flow from them. Thus assessments made purely on outcomes risk being unjust.

For example, an stock market trader might make an investment decision. They look at the available market data, check the fundamentals of the company, consider the potential risks and benefits, and look for any potential red flags. They decide to go ahead and invest a portion of their money, but in the end it doesn't work out and the trader loses out. In this instance, the outcome was poor, but despite this that the trader made a sound decision based on all the available information, their skills and experience. They also only invested a portion, so they still have money left to invest in something else.

By contrast, another trader might make an investment. They pick a stock at random and invest all of their money into it. By sheer good fortune the stock shoots up in price and the trader makes a significant return. The outcome was good, but can we really say the investor made a good decision? The outcome was down entirely to good luck, not any effort, skill or experience on the part of the investor. If they hadn't been so lucky, they might well have lost their entire portfolio. And given their success this time, there is a good chance they'll continue in the same way and push their luck.

Therefore as leaders we should assess people's actions and decisions by their quality, not the outcome. Now good quality decisions are more likely to lead to good outcomes as a general rule, so considering outcomes may assist us in assessing the quality, but it's not a given.

Fundamental Attribution Bias

Fundamental attribution bias relates to how we have a tendency to judge differently depending on whether we considering ourselves or somebody else. Let's take a situation where a person, either ourselves or somebody else makes a mistake when driving.

If it's somebody else who has made the mistake, we are more likely to attribute that mistake to that person's characters or personality, who they are as a person. We might say they are reckless, or inattentive or a poor driver, and that's probably the way they usually drive.

However, if it's ourselves who have make the mistake, we are much more likely to attribute that mistake to situational factors, particularly those that are external to ourselves. We might say we the sun was in our eyes, or that we were distracted by a passenger, or that we were particularly tired that day, and that normally our driving is of high standard.

We say they are lazy, we are fatigued, they weren't paying attention, we were distracted, they're an angry person, we were provoked.

As leaders we want to try to stay consistent between how we judge others compared to how we judge ourselves, and watch for fundamental attribution bias. It's not that we cannot made assessments of character as opposed to situational factors, but we should be aware when we are. We should also be cautious about attributing people's actions to character or personality traits before considering the full context. Is this a pattern of behaviour? Or were they having a bad day?

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is our tendency to look for, interpret, prefer and remember information that supports or confirms our own beliefs or expectations. If we believe for example that red wine is good for you in moderation, we are more likely to notice and remember the articles or news reports that support that idea and discount or not notice those that don't. On the other hand if we believe that red wine is a net negative, then the article or news reports supporting that will more likely receive our attention and preference.

The more we desire a particular outcome or the more deeply entrenched a belief, the stronger the potential for confirmation bias. This effect has been noticed in police investigations for example. The police believe the suspect is guilty, perhaps because they have arrested them for similar crimes before. This leads them to look for and prefer evidence that confirms their suspect is the guilty party, and are less likely to notice, and more likely to discount, evidence that suggests they have the wrong person. This is not to say the police are deliberately biassing the investigation (although that sometimes does happen), but rather it is a subconscious cognitive effect.

Confirmation bias can appear in all sorts of decisions, workplace conduct investigations, choice of vendor, assessment of customer reviews and so on.

As leaders we can't turn off confirmation bias, we have to wrestle with it. Being aware of it is the first step. If we have a strong belief, expectation or desire, this can be a flag to be on guard for confirmation bias. Training in critical thinking skills and decision making frameworks is also helpful. Involving others in the decision or assessment can also assist, especially if they don't have the same level of belief, expectation or desire that we have.

Conclusion

There are many more cognitive biases and other influences on our carefully reasoned decisions. But by knowing these four and being on the lookout for their appearance, either in ourselves or others, we can significantly improve the quality of our decision making and the trust of our teams. Leaders with awareness of cognitive biases are an important factor in building a just and fair learning culture in any organisation.

Was this post useful or interesting for you?

You can drop a comment on this post on LinkedIn, and if you think it would be helpful for others, please consider sharing it.

DISCLAIMER: This blog provides general information only, and is not intended as advice (legal or otherwise) specific to your circumstances. Please contact us if you have any particular questions.